The word protein is derived from the greek word protos meaning ‘first’, as protein is the basic material of all living cells. [1]

Without protein we do not exist, so it seems like it’s pretty damn important, right?

It’s become more evident within the past 5 or so years that protein is very important, probably partly fuelled by a general increase in gym memberships and people getting more health conscious.

And one common topic of conversation, certainly one I get as a trainer a lot is whether it’s safe to consume a high protein diet. So we’re going to take a look at the evidence for and against high protein diets.

Protein: A Brief Primer

Protein is the fundamental building blocks of our body and makes up the majority of muscle mass at around 70% [3]. Of all the macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins & fats) protein is the only one to contain nitrogen.

It is nitrogen that provides the basis for amino acids which are the ‘building blocks’ of essentially all lifeforms - nitrogen being the ‘amino’ part. [16]

All proteins are made up of chains of amino acids, often hundreds, and to digest proteins our body must break down them down into their respective amino acids for use within cells.

Amino acids are extremely important for many bodily functions including the production of:

- Enzymes (for chemical reactions such as digestion)

- Structural proteins (cells and tissue, muscle etc)

- Antibodies (to protect us from illness)

- Protein hormones (insulin, growth hormone and more)

- Transport (proteins to transport substances in the blood)

Nitrogen plays an important part in this article as it is traditionally said that having a positive nitrogen balance - i.e. nitrogen input greater than nitrogen output - results in a state of growth. [4]

As a bodybuilder this is certainly something that appeals to me, as I’ve always tried to maintain a positive nitrogen balance by eating a higher protein diet split into several meals throughout the day.

Yet nitrogen is also very important in the context of this article as one of its resulting breakdown products and methods of transport in the body is urea - which is excreted in urine but also processed in the kidneys.

The Risks of a High Protein Diet

When we talk about risks associated with protein intake we are typically talking about [1]:

- The kidneys, as you can probably guess from the last point; and producing unhealthy levels of urea & ammonia - the primary forms of nitrogen transport in the body[17] - making harder work for the kidneys and potentially resulting in a decrease in renal (kidney) function. This is measured from urine samples.

- The possible increase in acidity of the blood, and subsequent ‘buffering’ resulting in a loss of calcium from the bone, and therefore decreased bone health. Measured through blood samples.

- Possible increased risk of cancer through elevated IGF–1 hormone activity.

- Obesity from increased protein intake.

It should also be noted that increased protein intake has been suggested to create a dehydrating effect in the body due to kidneys being overworked, although there isn’t currently enough research to focus on the theory, and where studied has not been proven to have an effect, therefore we will not be addressing it in this article.

Many consider this negative effect ‘bro science’ - a common myth still repeated in the weight training world. My advice would be to ensure you’re hydrated at all times, drinking at least 1.5 litres of water a day; even if you’re not on a high protein diet, which is common sense really.

How much Protein is recommended?

To remain unbiased, let’s take a quick look at some various daily recommendations for protein levels based on adults age 18 - 50 years, as there’s quite a few out there and it’s often confusing which one you should follow:

- UK RNI, Food Standards Agency: 55 grams. [5]

- US DRV, Food & Drug Administration: 50 grams [6]

- Athlete focused study: 1.3–1.8g per kg of bodyweight [7]

Looking at these amounts you may be surprised how much over the daily recommended value (DRV) or reference nutrient intake (RNI previously RDA) you may be. If you consume a high protein, low carb meal with meat such as chicken or steak it’s very easy to consume 30–40 grams of protein, and that’s just in one meal. But it’s clear here that the government recommendations are only for those who lead sedentary lifestyles and want to ‘maintain’ bodyweight.

The government recommendations can make you think you might be ‘overdosing’ but in reality the athlete focused study is much closer to what people who train - whether that’s CrossFit, running or bodybuilding - consume, and is certainly a commonly recommended figure (I use it in many of my diet plans).

So assuming you weigh 65 kilos and were going for the higher level of protein, you’d be consuming 117 grams of protein per day.

So can this be bad for you?

Let’s take a look at the evidence currently out there for each case.

The Evidence - Is High Protein Bad for You?

Kidneys and Bones

A study by Portmans & Dellalieux [8] on bodybuilders consuming high protein found that when daily protein intake exceeded 1.26 g/kg bodyweight the athletes were in a positive nitrogen balance, and not only that but with doses less than 2.8g/kg there was no impact on kidney function. However, this study also found that there was in fact an increase in acidity and therefore calcium in the blood, possibly suggesting that high protein does support the theory of decreased bone health.

One of the issues with that study was the subjects are all bodybuilders, and therefore probably exposed to a high protein diet and less likely to show adverse reactions. Although, this may suggest something about those already on a high protein diet.

A study by Beasley & colleagues looked at postmenopausal women and found that there was no evidence for impaired renal function when higher protein levels were consumed, and another from Knight & colleagues studied women between the ages of 42–68 and concluded that there was also no impaired function [9, 10]. Both these studies however used lower protein levels than recommended for athletes at roughly 1.1g/kg (still higher than recommended amounts for women of these ages).

On a similar level of protein intake, a study on healthy males using 1.2g or 2.4g per kilogram of bodyweight found that there was in fact increased uric acid in the higher protein sample group, indicating that there could be renal function impact in only the high protein group, although this study was short at only 7 days [11]. Again, a dosage of 1.6g/kg of bodyweight in a 2 week trial by Weigmann and colleagues showed no signs of affecting kidney health [12].

Back to bone health, Calvez et al [13] looked at whether high protein diets created an environment in the body detrimental to bone health, and found no evidence to support the theory, providing diets are not deficient in calcium. Furthermore, they concluded that protein can actually have a positive effect on bone growth and slow down bone loss, as well as have no negative effect on renal function.

You might think at this point that the major research shows there is no strong evidence to support claims that bone or kidney health can be harmed by high protein intakes, and you’d be right. But there is one factor that seems to be evident from almost all these studies: there is an effect on kidney function if your kidneys are not currently functioning at a healthy level.

So essentially, if you have serious health conditions effecting your kidneys such as chronic kidney disease, a high protein diet should be avoided.

Cancer and Obesity

When it comes to a possible increase in the risk of cancer through a high protein diet, we are specifically talking about the role of insulin-like growth factor–1 (IGF–1) and the increase or decrease of its activity. IGF–1 is actually a hormone which plays a key role in anabolic growth, particularly in adults, and is directly linked to growth hormone - having an effect on the growth of almost all types of cells in the body.

You’ve probably read many times about the benefits of a vegan diet, and how a vegan diet can potentially decrease the risks of cancer. This is largely linked to IGF–1 production, and the fact that certain vegan proteins (soy for example) stimulate much less of an insulin response due to their amounts of essential amino acids being much lower than animal proteins.[18]

This is still highly debated however, largely due to mixed messages from many of the studies. For example, a study by Levine, M. and colleagues in 2014 [19] correlated a decreased risk of cancer from low protein plant based diets for adults 50–65 years of age, yet an increased risk of cancer for those over the age of 65. The study classed high protein consumption as over 20% of daily caloric intake derived from protein, and low protein consumption 10% of calories or under - suggesting that in older populations high protein diets actually contribute to lower risk of cancer. 20% of daily calories from protein works out at 125 grams based on a 2500 calorie day. You’ll probably recognise this study as it was hugely popular in the media, with newspapers stating headlines as misleading as ‘Diets high in protein could be as harmful to health as smoking’, which if you’d read the study is slightly blown out of proportion due to the fact they didn’t even mention the second part about over 65’s.

It can be said that the hypothesis of these articles is actually something that makes sense, particularly as increased caloric consumption can be associated with increased IGF–1 levels and therefore cell growth, but it’s associated with ALL cell growth, not just cancerous cells [20]. There is more evidence needed for the relationship of cancer and high protein diets, but we can say that an increase or decrease in protein levels in the diet will be associated with IGF–1 production respectively [21]. This is also closely linked to the mTOR signalling pathway, also activated through IGF–1 increases and closely associated with higher free amino acid levels in the body (increased protein intake). This has been suggested to be linked to faster ageing, but much more evidence is needed to support this theory, particularly when focusing on protein rather than overall caloric intake. [22,23].

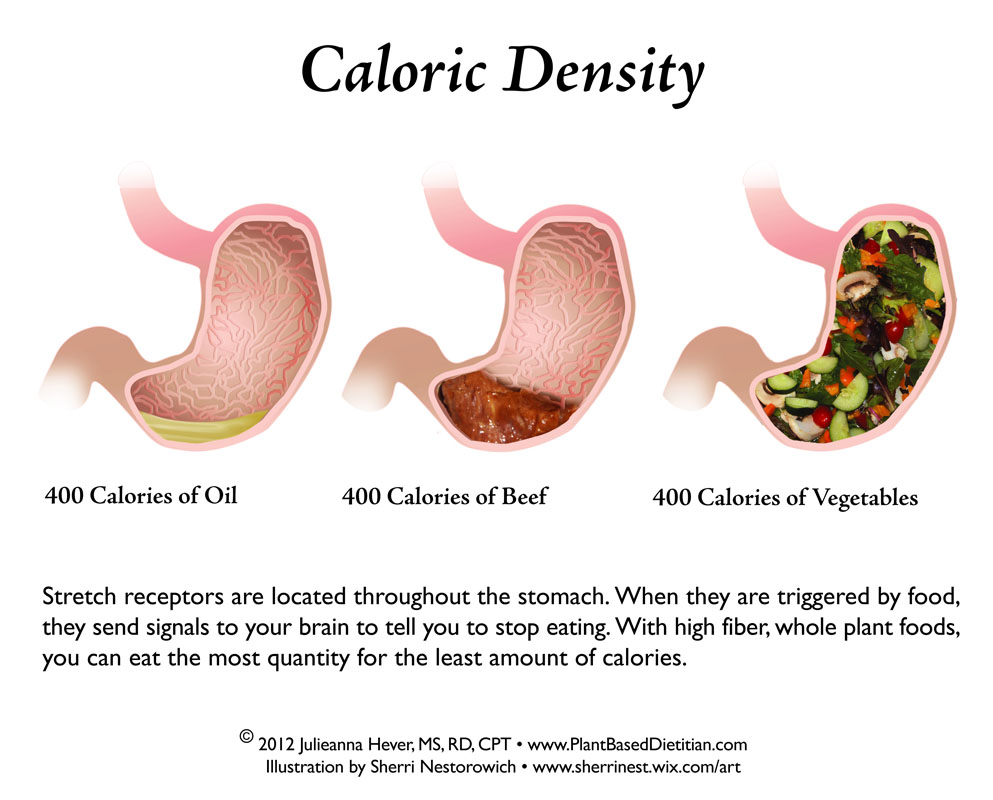

Focusing on obesity and its link to high protein diets, I was particularly impressed by the level of detail Garth Davis went into on the subject in his recent book Proteinaholic. Although the level of detail in the book is excellent, more importantly he manages to make it simple and clear how protein is linked to obesity, and that’s largely through caloric density, a concept many of you may be familiar with.

Image credit: https://plantbaseddietitian.com/tag/fiber/

Essentially, vegetables are much more dense and will fill you quicker, activating the ‘stretch response’ and letting our brains know we should stop eating. With a meal that is higher in protein, this effect is a much slower process, meaning we’ll end up eating more and generally ingesting more calories, resulting in weight gain. Long term this could of course lead to obesity.

But I found the main takeaway from Proteinaholic was not that protein is necessarily the bad guy, but that a high protein diet can lead to obesity in the long term, through increased caloric intake.

TL;DR

For each hypothesised side effect from high protein consumption we found the following evidence:

- Decreased renal function: limited evidence to support the theory, and if you’re a healthy individual, high protein intakes should have no effect on kidney function. Although it is highly advised to not consume more than 2.8g protein per kg of bodyweight (something quite hard to do anyway).

- Decreased bone health: again limited evidence to support this theory, even less so than renal function impairment.

- Increased cancer risk: there is a direct link to increased risk of cancer through increased cellular growth from higher protein diet in those between the ages of 50–65 years of age, although more evidence is needed.

- Obesity: a more common sense approach; consumption of high protein diets are more likely to result in us consuming a higher amount of calories in general. Long term this will result in obesity.

Conclusion

The phrase ‘too much’ will always mean an excess of something, but we should stop throwing it around and give specifics. If you are a trainer or dietician it is not good advice to say ‘don’t eat too much protein’. And in the case of very high protein there does seem to be some negative effect on the body, particularly the kidneys and bones; but only if we consume in excess of 1.8 grams of protein per kilogram of bodyweight per day for an extended period of time.

Overall recommendations are to ensure that if you are increasing your protein intake, you are also eating a balanced diet all round, so that your caloric intake isn’t skewed towards one macronutrient group - in this case protein.

Essentially we are confirming, once again, how important it is to eat your greens!

Let us know your thoughts

How much protein do you consume daily? Are you ever concerned for your health when consuming high protein daily? We’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments or over on our Facebook page.

References

1 - The Optimum Nutrition Bible, Patrick Holford; 1997

2 - Earl Mindells New Vitamin Bible; 2011

3 - Nitrogen Balance, 2005; David Robson

4 - David A Bender, 2006; Dept of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology; UCL

6 - Guidance for Industry: a food labelling guide, FDA; 2013

7 - Dietary protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation, Phillips & Van Loon; 2011

13 - Protein intake, calcium balance and health consequences, Calvez et al; 2012

15 - Dietary protein intake and renal function, Martin et al; 2005

16 - The Nutritionist - second edition, Robert Wildman, 2009.

22 - mTOR signaling at a glance, Mathieu Laplante, David M. Sabatini, 2009.

23 - mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing, Zoncu et al, 2010.

Be the first to comment